Formal theory of causality

| Subject classification: this is a philosophy resource. |

| Educational level: this is a research resource. |

This is a first-order theory of causality, so some familiarity with first-order logic is assumed. The goal of this theory is not to prove anything useful or unexpected, but to describe the structure of causal systems and to develop an elegant terminology to talk about causality.

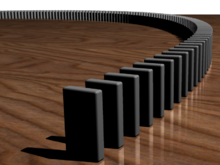

According to this theory, the structure of causal systems is probably that of a directed acyclic graph.[1]

This theory makes heavy use of the formal dictionary.

Preliminaries

[edit | edit source]- The domain of discourse is the set of all events.

- The letters c, d and e (with or without subscripts) are used as variables for events, instead of the usual x, y and z. The letter e is meant to evoke the word "event" and sometimes the word "effect". The letter c is meant to evoke the word "cause", and the letter d is meant to evoke some intermediate event between c and e. So often, c will be the cause of d, and d the cause of e.

- Every definition, axiom and theorem is first stated in natural language, then in formal language, and in the case of theorems, it's followed by a proof.

- For aesthetic reasons, external parenthesis and universal quantifiers are omitted.

- When defining a new term, the usual symbol is ":=", but here we use just ":" per being simpler, beautiful and consistent with dictionary practice.

Primitives

[edit | edit source]Big Bang

[edit | edit source]b is an individual constant with intended reading "Big Bang".

Event

[edit | edit source]This is a primitive term. You can help the formal dictionary by finding a good definition for it. |

Event is a primitive term, an undefined term used to define others. You can get an intuitive grasp of the intended meaning of the term by reading the article Event (philosophy) at Wikipedia.

Ex is a one-place predicate with intended reading "x is an event".

Cause

[edit | edit source]This is a primitive term. You can help the formal dictionary by finding a good definition for it. |

Cause is a primitive term, an undefined term used to define others. You can get an intuitive grasp of the intended meaning of the term by reading the article Cause at Wikipedia.

xCy is a two-place predicate with intended reading "x is a cause of y".

Definitions

[edit | edit source]

The definitions in this section are all taken from the Formal dictionary.

Effect

[edit | edit source]Let c and e be events. Then e is an effect of c means: c is a cause of e.

Direct cause

[edit | edit source]Let c, d and e be events. Then c is a direct cause of e means: c is a cause of e and there is no d such that c is a cause of d and d is a cause of e.

Indirect cause

[edit | edit source]Let c and e be events. Then c is an indirect cause of e means: c is a cause of e, but c is not a direct cause of e.

Causal independence

[edit | edit source]Let c and e be events. Then c is causally independent of e means: c is not a cause of e and e is not a cause of c.

First cause

[edit | edit source]Let e be an event. Then e is a first cause means: there is no event c that is a cause of e.

Full set of causes

[edit | edit source]Let e be an event and ε be a set of events. Then ε is a full set of causes of e means: for every event c that is a cause of e, c is an element of ε.

Causal chain

[edit | edit source]A sequence of events (e1, e2, e3 ..., en) is a causal chain means: e1 is a cause of e2, e2 is a cause of e3 and so on until en-1 is a cause of en

Axioms

[edit | edit source]The Big Bang is an event

[edit | edit source]

The Big Bang is a first cause

[edit | edit source]The Big Bang is a first cause.

Events have effects

[edit | edit source]Every event has at least one effect.

Causality is asymmetric

[edit | edit source]If event c is a cause of event e, then e is not a cause of c.

Causality is transitive

[edit | edit source]If event c is a cause of event d, and d is a cause of event e, then c is a cause of e.

Theorems

[edit | edit source]Simple equivalences

[edit | edit source]Let c and e be events. Then:

- c is a cause of e iff e is an effect of c

- c is a direct cause of e iff e is a direct effect of c

- c is a direct cause of e iff c is not an indirect cause of e

- c is an indirect cause of e iff e is not a direct cause of c

- e is a direct effect of c iff c is not an indirect effect of e

- c is an indirect cause of e iff e is an indirect effect of c

No event is a cause of itself

[edit | edit source]No event is a cause of itself (causality isn't reflexive).

For a proof by contradiction, suppose some event e is a cause of itself. Then by the axiom of asymmetry, e is not a cause of itself. But this is a contradiction, so no event can be a cause of itself. QED

Direct causes of the same effect are causally independent

[edit | edit source]If event c and event d are both direct causes of event e, then c and d are causally independent.

For a proof by contradiction, suppose c and d are both direct causes of e, but are not causally independent. Then c must be a cause of d, or d must be a cause of c, or both. It cannot be both, because causality is asymmetric. So suppose c is a cause of d. Then c is an indirect cause of e, as well as a direct cause. But this is a contradiction. The same happens if we suppose d is a cause of c. Therefore, c and d must be causally independent. QED

The Big Bang is in every full set of causes

[edit | edit source]The Big Bang is in every full set of causes.

Events are infinite

[edit | edit source]Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Proof needed.